India is not yet a rabies-free country despite decades of scientific clarity on how the disease can be eliminated. The tools are well known: mass dog vaccination, sustained coverage, and population stability. What continues to derail rabies eradication is not a lack of vaccines or knowledge, but a persistent misunderstanding of free-living dogs—and of the citizens who live alongside them.

At the heart of this failure lies a conceptual error: the assumption that India’s street dogs are feral animals, detached from human society and therefore best managed through removal, confinement, or suppression. Behavioural ecology, epidemiology, and India’s own rabies-control experience show this assumption to be false—and dangerous.

Street Dogs Are Not Feral—and This Distinction Matters

“Feral” animals are those that avoid humans and live independently of human systems (Read more). Research from India and elsewhere shows that the vast majority of free-living dogs do not fit this description.

Studies of free-ranging dogs demonstrate that they are human-associated, urban-adapted animals that live in stable social groups, occupy defined territories, and regularly interact with familiar humans (Bonanni et al., 2011; Bonanni et al., 2014). Indian studies further show that these dogs are highly sensitive to human social cues and capable of distinguishing friendly from threatening humans (Bhadra et al., 2016; Bhadra et al., 2018).

This behavioural profile directly contradicts the notion of ferality and has critical public-health implications. Vaccination-based rabies control works best precisely in populations that are visible, localised, and socially stable.

Mislabeling street dogs as feral leads to policy responses—removal, relocation, mass sheltering—that dismantle these very conditions.

Rabies Control Depends on Stability, Not Elimination

The global scientific consensus is unequivocal: rabies is controlled by vaccinating dogs, not by reducing dog numbers.

Classic and contemporary reviews show that culling and removal have no sustained impact on rabies transmission, because population turnover rapidly replaces removed dogs with susceptible animals (Beran & Frith, 1988; Hiby, 2013). Maintaining vaccination coverage of approximately 70% of the dog population is sufficient to interrupt transmission.

Empirical evidence from multiple countries demonstrates that indiscriminate removal can actually increase rabies incidence by lowering herd immunity and increasing dog movement (Windiyaningsih et al., 2004; Hossain et al., 2011).

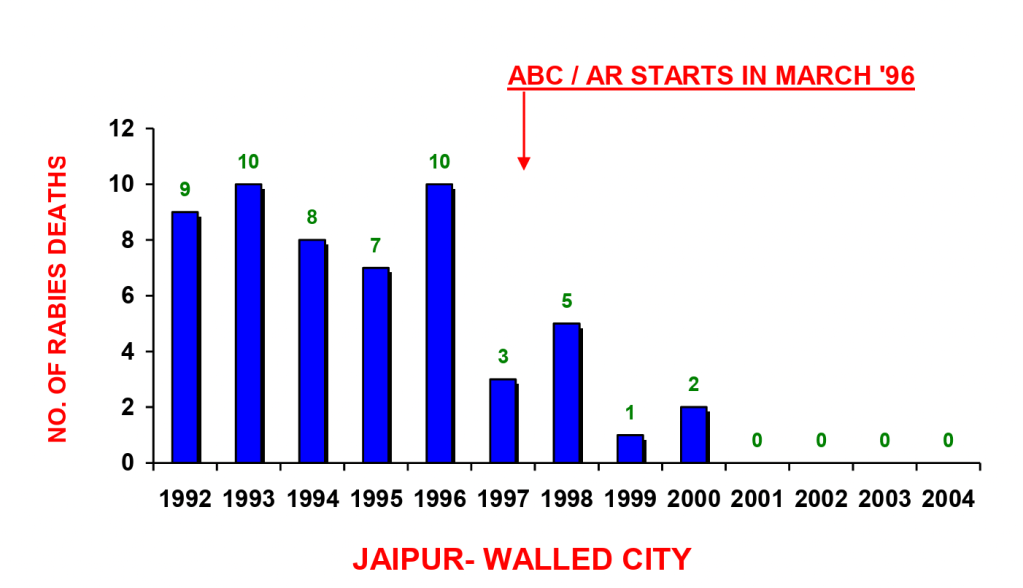

India’s own experience confirms this. Rabies control in Jaipur was achieved without eliminating free-living dogs, through sustained vaccination and sterilisation while dogs remained in their territories (Reece & Chawla, 2006).

ABC-AR Works in India—When Dogs Are Left in Place

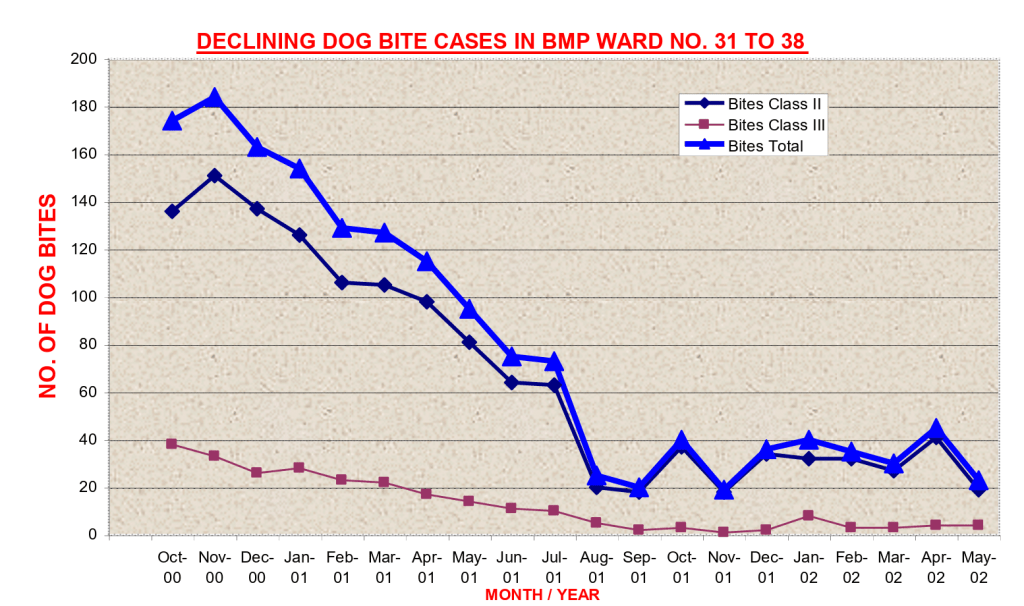

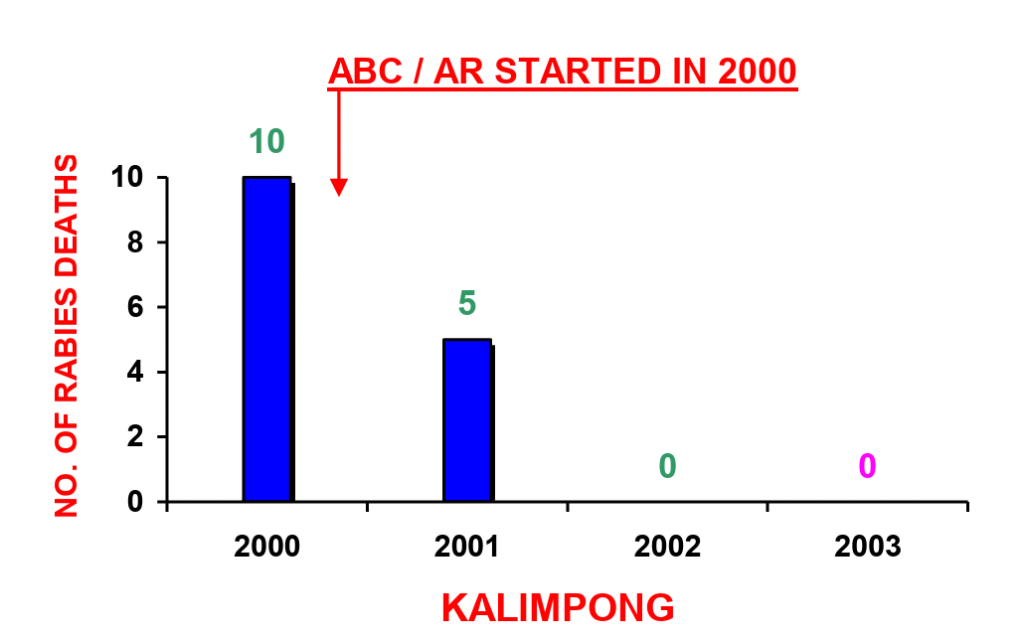

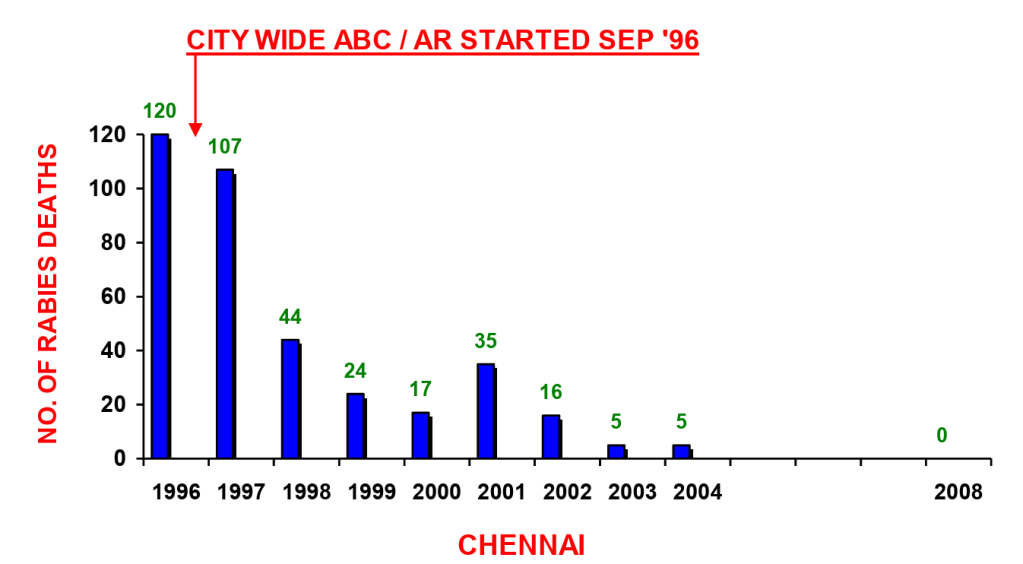

India’s Animal Birth Control–Anti-Rabies Vaccination (ABC-AR) programme is often criticised for “failing,” yet peer-reviewed evaluations show that where it is implemented correctly, it works.

Krishna (2010) documents the success of ABC-AR in reducing rabies incidence without removing dogs from the streets. Crucially, these successes depended on:

- Dogs remaining in their original territories

- Repeat vaccination over time

- Community cooperation and tolerance

Presented below are graphs of success of ABC-ARV in places where it is implemented correctly.

Mission Rabies’ long-running programme in Goa, initiated in 2013 in partnership with the state government, demonstrates what sustained high-coverage dog vaccination can achieve. Through repeated annual campaigns, Mission Rabies has vaccinated millions of dogs across the state, contributing to a dramatic reduction in rabies risk. In recognition of these outcomes, Goa was declared a “Rabies Controlled Area” in 2021, becoming the first Indian state to achieve this status through a strategy centred on mass dog vaccination, surveillance, and community engagement rather than dog elimination .

Similar outcomes have been reported in other Indian cities where Mission Rabies has implemented long-term vaccination and education programmes. In Ranchi, Jharkhand, sustained dog vaccination and community outreach have been associated with zero reported human rabies deaths for multiple consecutive years, despite the continued presence of free-living dogs. Large-scale campaigns in cities such as Bengaluru, where tens of thousands of dogs have been vaccinated annually, further demonstrate that even dense urban environments can achieve meaningful coverage when dogs are accessible, localised, and familiar to communities (Mission Rabies, 2021).

The failure of rabies control in many regions is therefore not evidence against ABC-AR, but evidence of poor implementation and policy drift toward removal-based thinking.

Citizen Care Makes Vaccination Possible at Scale

Vaccinating the free-living dog population is logistically viable precisely due to the citizen caregivers. Hence their value is not to be overlooked in this process.

Research on dog population management consistently shows that community participation improves vaccination access, coverage, and cost-effectiveness (Hiby, 2013; Tenzin et al., 2015).

Caregivers:

- Anchor dogs to specific locations

- Make dogs approachable and identifiable

- Assist in humane capture for sterilisation and vaccination

- Enable static-point administration that eliminates needs for catchers, who are the biggest expense in this program (Sánchez-Soriano, C., et al. 2019, Fitzpatrick, et al. 2016).

- Enable post-operative care and long-term monitoring

From a public-health perspective, citizen care functions as distributed surveillance and access infrastructure—a role no centralised system can replicate at India’s scale.

Feeding Does Not Increase Risk—It Reduces It

A persistent myth in rabies discourse is that feeding street dogs increases aggression and bite risk. Behavioural science does not support this claim.

Studies show that aggression is typically linked to fear, injury, social disruption, or human provocation, not to regular feeding or familiarity (Bonanni et al., 2011; Bhadra et al., 2016).

Discouraging feeding does not make dogs disappear. It makes them hungrier, more stressed, more mobile, and harder to vaccinate, while simultaneously undermining rabies surveillance. In contrast, well feed dogs are calmer, more approachable, content and thus less prone to dysregulation and resulting conflict.

Relocation and Mass Sheltering Are Scientifically Unsound

Large-scale relocation and long-term sheltering seem to be promoted as “humane” alternatives. Scientific evidence strongly contradicts this framing.

Disrupting dog social groups increases stress and conflict (Bonanni et al., 2014), while concentrating dogs in confined environments elevates disease risk. Removal also undermines vaccination coverage by eliminating immunised dogs and accelerating population replacement (Beran & Frith, 1988; Hiby, 2013).

From both epidemiological and behavioural perspectives, keeping vaccinated dogs in place is safer than removing them.

From Tolerating Citizens to Partnering With Them

The evidence no longer supports asking whether citizen care can be part of rabies eradication. It already is.

Rabies will not be eradicated in India by treating compassion as a liability or by pretending that free-living dogs are feral intruders in human space. It will be eradicated by working with the social reality that already exists: millions of citizens coexisting with, caring for, and stabilising local dog populations every day.

Encouraging, protecting, and formally integrating citizen care into rabies-control strategies is not a sentimental choice. It is the most scientifically grounded, economically viable, and ethically defensible path available.

India does not need to invent a new solution to rabies. It needs to stop dismantling the one it already has.

About The Authors

Sindhoor is a canine behaviour consultant, a canine myotherapist, an anthrozoologist and an engineer by qualification. She researches free living dogs in Bangalore, India. She has presented her findings at major international conferences in the US, UK and has conducted seminars in Europe, UK and South America. She has been invited as an expert on several podcasts, including a few on NPR radio. She maintained a weekly column on dog behaviour, in The Bangalore Mirror for two years. She is a TEDx speaker, the author of the book, Dog Knows. National Geographic calls hers a ‘Genius Mind’ in the bookazine, Genius of Dogs. She is currently the principal and director of BHARCS. BHARCS offers a unique, UK-accredited level 4 diploma on canine biosociopsychology and applied ethology.

References

- Beran, G. W., & Frith, M. (1988). Domestic animal rabies control: An overview. Reviews of Infectious Diseases.

- Bhadra, A., et al. (2016). Free-ranging dogs are socially responsive to humans. Scientific Reports.

- Bhadra, A., et al. (2018). Free-ranging dogs understand human social cues. PLOS ONE.

- Bonanni, R., et al. (2011). Social organisation in free-ranging dogs. Behavioural Ecology.

- Bonanni, R., et al. (2014). Social disruption and aggression in dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science.

- Fitzpatrick, et al. (2016) One Health approach to cost-effective rabies control in India.

- Hiby, E. (2013). Dog population management. CAB International.

- Krishna, C. S. (2010). The success of the ABC-AR programme in India.

- Mission Rabies. India Projects – Goa Rabies Control Programme; State declared Rabies Controlled Area (2021).

- Mission Rabies. India Projects – Ranchi and Bengaluru vaccination campaigns.

- Reece, J. F., & Chawla, S. K. (2006). Rabies control in Jaipur. Veterinary Record.

- Sánchez-Soriano, C., et al. (2019) Development of a high number, high coverage dog rabies vaccination programme in Sri Lanka.

- Tenzin, T., et al. (2015). Rabies control in free-roaming dogs. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.

- Windiyaningsih, C., et al. (2004). Rabies epidemic on Flores Island.

One thought on “Why Citizen-care of Free-Living Dogs Is a Public-Health Necessity”