The idea that dogs can “smell fear” and will attack fearful people is deeply embedded in popular culture. You’ve probably heard it as advice: “Don’t show fear around dogs or they’ll bite you.” But what does science actually tell us? The research challenges this myth and shows us that human behaviour, not canine aggression toward fear, is the real driver of most dog-human conflicts.

1. Do Dogs Sniff Fear, and What Happens When They Do?

Yes, dogs can detect human fear through chemical signals. Multiple experimental studies have exposed dogs to human fear chemosignals—axillary sweat collected from people experiencing fear versus neutral or happy emotional states. The results consistently show that dogs perceive these fear odours and respond to them, but not in the way popular wisdom suggests.

When dogs detect human fear scent, they display a constellation of behaviours that indicate discomfort and caution, not aggression. Rather than charging toward the source of fear, dogs tend to slow their approaches, stay closer to trusted humans, and show higher rates of disengaging from tasks altogether.

The predominant canine response to human fear is not “attack the vulnerable person” but rather caution, safe-haven seeking, and hesitation. Dogs experience low-level uncertainty when they detect fear, often expressed through attachment behaviors to known humans—the opposite of predatory aggression. This research fundamentally challenges the notion that fearful people are at greater risk of dog attacks simply because of their emotional state.

2. How Dogs Actually Interact with Humans

Understanding real-world dog-human interactions requires looking beyond laboratory conditions to observe how free-living dogs navigate complex urban environments. Research on street dogs in Indian cities—where dogs face both positive interactions like feeding and petting, and negative ones like chasing and threatening—reveals sophisticated social cognition.

Field experiments using standardized human cues show that dogs read human intentions with remarkable precision. When unfamiliar humans displayed friendly approaches, dogs readily approached with short pauses, high rates of tail wagging, and friendly, sociable demeanor. Under high-impact threats (such as a raised stick), dogs showed anxious demeanor, increased distance, and very low approach rates—even when food was later offered.

Time-budget studies paint an even clearer picture: free-ranging dogs are generally inactive and non-conflictual around humans. In observations of 1,941 dog sightings across Indian towns, dogs were inactive in over half of observations, with only about 14% of time involving any interactions or vocalizations. Human interactions were extremely rare and entirely submissive or begging-type—not aggressive.

Dogs rapidly learn which individual humans are rewarding. In multi-day experiments where two unfamiliar women stood side-by-side but only one provided food and petting, dogs chose the rewarding person significantly above chance after just four brief interactions. Their socialization behaviors—tail wagging, contact-seeking, affiliative vocalizations—were significantly higher toward the rewarding individual, even on test days when neither woman had food.

Perhaps most importantly, humans are the primary initiators of both affiliative and antagonistic encounters. Observational research consistently finds that people initiate most dog-human interactions—feeding, petting, chasing, or threatening—while dogs typically respond with approach, begging, or retreat. The structure and tone of these interactions is set by human behavior, not canine aggression. Dogs approach humans who signal safety and reward, and avoid those who appear threatening—regardless of whether the human is afraid.

3. Why Dogs Actually Bite: Causes of Defensive Reactions

If fear detection doesn’t trigger attacks, what does cause dogs to bite? Current research identifies most bites and “aggressive” reports as stress- or fear-driven defensive reactions that can be prevented through early recognition and environmental management.

When we see growling, barking, lip lifting, body stiffening, and showing teeth, we are witnessing fearful signals from a dog who is experiencing fear themselves, not detecting fear in humans. Studies of dogs in such instances describe low postures, ears and tails down, growling and snapping when approached or touched—classic defensive behaviour. In shelter and clinical samples, many dogs labeled aggressive are actually fearful animals in stressful settings whose aggression resolves or improves markedly when the cause of their fear is removed.

A single snap or bite when a dog is cornered, in pain, or harassed fits the definition of fear- or pain-elicited aggression and is not, by itself, evidence of an “aggressive dog.” These defensive reactions are most likely in specific contexts:

Fear and stress: Dogs who are experiencing fear typically react when people approach them aggressively, corner them, or crowd them—especially in confined spaces or around resting areas. These reactions are often misread as “random” aggression.

Human harassment or abuse: Dogs with histories of abuse show higher stranger-directed fear making them more likely to react defensively to unfamiliar people or dogs.

Chaotic environments: In shelters, fearful dogs frequently fail aggression screenings despite not being generally aggressive. Brief positive human-interaction enrichment substantially reduces fear-induced aggression.

Handler error: Inconsistent or excessive punishment and poor communication from humans maintain or worsen defensive reactions, rather than resolve it.

Resource Guarding: Dogs with insecurities around basic resources can get protective of them and react defensively.

Pain and poor health: Pain and health issues have been identified as a common underlying reason for “aggression”.

4. How to Prevent Dog Bites

Prevention requires addressing root causes rather than removing dogs. Observations strongly supports interventions that reduce fear and stress while managing the environment:

Stable, low-conflict feeding and resting areas: Reducing crowding and reduced competition over food lowers resource-guarding and frustration—both recognised bite-triggers. Designated feeding areas should provide sufficient space for all dogs to eat comfortably, be located away from heavy human activity, and maintain cleanliness to avoid attracting other animals.

Medical care: Pain, chronic disease, and hormone-linked factors increase bite risk. Timely vaccinations, sterilisations, and regular health checks address medical contributors that must be resolved.

Positive human-dog relationships: Programs centered on calm, predictable human interaction reduce physiological stress in dogs.

Community education: Communities should learn to recognise early warning signals that are requests for space, not preludes to attack. People should avoid sudden movements, never corner dogs, and understand that barking isn’t aggression, but communication. Children need supervision around all animals and should be taught to “stand still like a tree” if approached by any animal. Elderly residents benefit avoiding feeding or resting areas.

Final Thoughts

The myth that dogs smell fear and attack the fearful is more than just misinformation—it’s a narrative that puts both humans and dogs at risk. It places blame on vulnerable people for being afraid while absolving us of responsibility for our own threatening behaviors. The research tells a different story: dogs are sophisticated readers of human intention who respond to what we do, not what we feel. They approach us when we’re rewarding and kind, and they defend themselves when we’re threatening or abusive.

Most bites aren’t about aggression at all—they’re desperate requests for space from frightened animals in stressful situations. When we understand this, prevention becomes clear: create safe spaces for dogs to rest and eat, provide medical care, stop harassing and intimidating them, and educate communities to recognize stress signals before they escalate.

The power to prevent dog bites has always been in our hands, not in managing our fear. It’s time we took responsibility for the role we play in these conflicts and built the compassionate, informed communities that both humans and dogs deserve.

About The Authors

Sindhoor is a canine behaviour consultant, a canine myotherapist, an anthrozoologist and an engineer by qualification. She researches free living dogs in Bangalore, India. She has presented her findings at major international conferences in the US, UK and has conducted seminars in Europe, UK and South America. She has been invited as an expert on several podcasts, including a few on NPR radio. She maintained a weekly column on dog behaviour, in The Bangalore Mirror for two years. She is a TEDx speaker, the author of the book, Dog Knows. National Geographic calls hers a ‘Genius Mind’ in the bookazine, Genius of Dogs. She is currently the principal and director of BHARCS. BHARCS offers a unique, UK-accredited level 4 diploma on canine biosociopsychology and applied ethology.

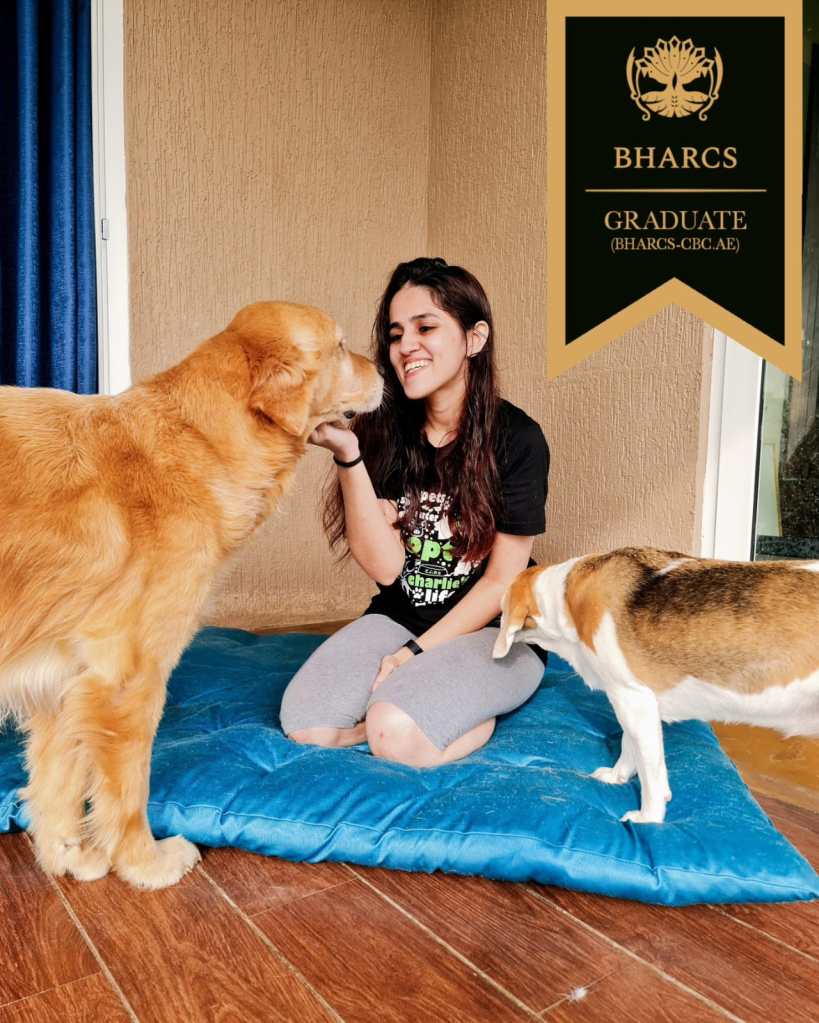

Sowjanya Vijayanagar

Sowjanya is a certified Canine Behaviour Consultant, Applied Ethologist, and founder of Dog Pawmise (est. 2020), where she works with dog care-givers to build harmonious, connection-based relationships with their dogs using a biosociopsychological approach. She holds the BHARCS Applied Canine Biosociopsychology and Ethology Diploma from BHARCS, India, specialising in canine communication and human-dog interactions.

References

Abdai, J., Bartus, D., Kraus, S., Gedai, Z., Laczi, B., & Miklósi, Á. (2022). Individual recognition and long-term memory of inanimate interactive agents and humans in dogs. Animal Cognition, 25(6), 1427-1442.

Bhattacharjee, D., & Bhadra, A. (2020). Humans dominate the social interaction networks of urban free-ranging dogs in India. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2153.

Bhattacharjee, D., & Bhadra, A. (2022). Adjustment in the point-following behaviour of free-ranging dogs–roles of social petting and informative-deceptive nature of cues. Animal Cognition, 25(3), 571-579.

Bhattacharjee D, Mandal S, Shit P, Varghese MG, Vishnoi A and Bhadra A (2020) Free-Ranging Dogs Are Capable of Utilizing Complex Human Pointing Cues. Front. Psychol. 10:2818. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02818

Bhattacharjee, D., N, N. D., Gupta, S., Sau, S., Sarkar, R., Biswas, A., … & Bhadra, A. (2017). Free-ranging dogs show age related plasticity in their ability to follow human pointing. PloS one, 12(7), e0180643.

Bhattacharjee, D., Sau, S., & Bhadra, A. (2018). Free-ranging dogs understand human intentions and adjust their behavioral responses accordingly. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 232.

Biswas, S., Ghosh, K., Gope, H., & Bhadra, A. (2025). Fair game: Urban free-ranging dogs balance resource use and risk aversion at seasonal fairs. Current Zoology, zoaf030.

Bhattacharjee, D., Sarkar, R., Sau, S., & Bhadra, A. (2019). A tale of two species: How humans shape dog behaviour in urban habitats. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.07113.

Biswas, S., Ghosh, K., Ghosh, S., Biswas, A., & Bhadra, A. (2025). What is in a scent? Understanding the role of scent marking in social dynamics and territoriality of free-ranging dogs. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 79(1), 3.

Capitain, S., Range, F., & Marshall-Pescini, S. (2025). Not just avoidance: Dogs show subtle individual differences in reacting to human fear chemosignals. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 12, 1679991.

Csepregi, M., & Gácsi, M. (2023). Factors contributing to successful spontaneous dog–human cooperation. Animals, 13(14), 2390.

D’Aniello, B., Pinelli, C., Scandurra, A., Di Lucrezia, A., Aria, M., & Semin, G. R. (2023). When are puppies receptive to emotion-induced human chemosignals? The cases of fear and happiness. Animal Cognition, 26(4), 1241-1250.

Ferreira, A., Pereira, M., Agrati, D., Uriarte, N., & Fernández-Guasti, A. (2002). Role of maternal behavior on aggression, fear and anxiety. Physiology & behavior, 77(2-3), 197-204.

Franzini de Souza, C. C., Dias, D. P. M., Souza, R. N. D., & Medeiros, M. A. D. (2018). Use of behavioural and physiological responses for scoring sound sensitivity in dogs. PloS one, 13(8), e0200618.

Fromm, E. (1968). Excerpt of Moyer, KE, 1968:> Kinds of Aggression and their Physiological Basis,< in: Communications in Behavioral Biology, Part A, Vol. 2 (No. 2, August 1968), pp. 65-87.

Galac, S., & Knol, B. W. (1997). Fear-motivated aggression in dogs: patient characteristics, diagnosis and therapy. Animal Welfare, 6(1), 9-15.

Gazzano, A., Migoni, S., Guardini, G., Bowen, J., Fatjò, J., & Mariti, C. (2015). Stress in aggressive dogs towards people: Behavioral analysis during consultation. Dog behavior, 1(3), 6-13.

Jacobs, J. A., Coe, J. B., Pearl, D. L., Widowski, T. M., & Niel, L. (2018). Factors associated with canine resource guarding behaviour in the presence of people: A cross-sectional survey of dog owners. Preventive veterinary medicine, 161, 143-153.

Jakovcevic, A., Elgier, A. M., Mustaca, A. E., & Bentosela, M. (2013). Frustration behaviors in domestic dogs. Journal of applied animal welfare science, 16(1), 19-34.

Majumder, S. S., Chatterjee, A., & Bhadra, A. (2014). A dog’s day with humans–time activity budget of free-ranging dogs in India. Current Science, 874-878.

McMillan, F. D., Duffy, D. L., Zawistowski, S. L., & Serpell, J. A. (2015). Behavioral and psychological characteristics of canine victims of abuse. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 18(1), 92-111.

Meints, K., Brelsford, V., & De Keuster, T. (2018). Teaching children and parents to understand dog signaling. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 257.

Nandi, S., Chakraborty, M., Lahiri, A., Gope, H., Bhaduri, S. K., & Bhadra, A. (2024). Free-ranging dogs quickly learn to recognize a rewarding person. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 278, 106360.

Parr-Cortes, Z., Müller, C. T., Talas, L., Mendl, M., Guest, C., & Rooney, N. J. (2024). The odour of an unfamiliar stressed or relaxed person affects dogs’ responses to a cognitive bias test. Scientific reports, 14(1), 15843.

Pedretti, G., Canori, C., Biffi, E., Marshall-Pescini, S., & Valsecchi, P. (2023). Appeasement function of displacement behaviours? Dogs’ behavioural displays exhibited towards threatening and neutral humans. Animal cognition, 26(3), 943-952.

Reisner, I. R., Shofer, F. S., & Nance, M. L. (2007). Behavioral assessment of child-directed canine aggression. Injury Prevention, 13(5), 348-351.

Siniscalchi, M., d’Ingeo, S., Minunno, M., & Quaranta, A. (2018). Communication in dogs. Animals, 8(8), 131.

Tortora, D. F. (1983). Safety training: the elimination of avoidance-motivated aggression in dogs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 112(2), 176.

Willen, R. M., Schiml, P. A., & Hennessy, M. B. (2019). Enrichment centered on human interaction moderates fear-induced aggression and increases positive expectancy in fearful shelter dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 217, 57-62.

Dear Sindhoor,

This is the best blogpost I have read in many years in regard to the theme you researched so well!

My appreciation en hope it wil give the mass some food for thought.

What I also want to include is that trauma within family ( lineage) and in mostly purbred dogs are in my vision also a reason why many can bite without u true threat. There nervsystem doesn’t function well because of a high unhealthy stress level.

All goods from a Canine admire.

LikeLike